The Great Flood, part 2

THE GREAT FLOOD OF 2039, part 2

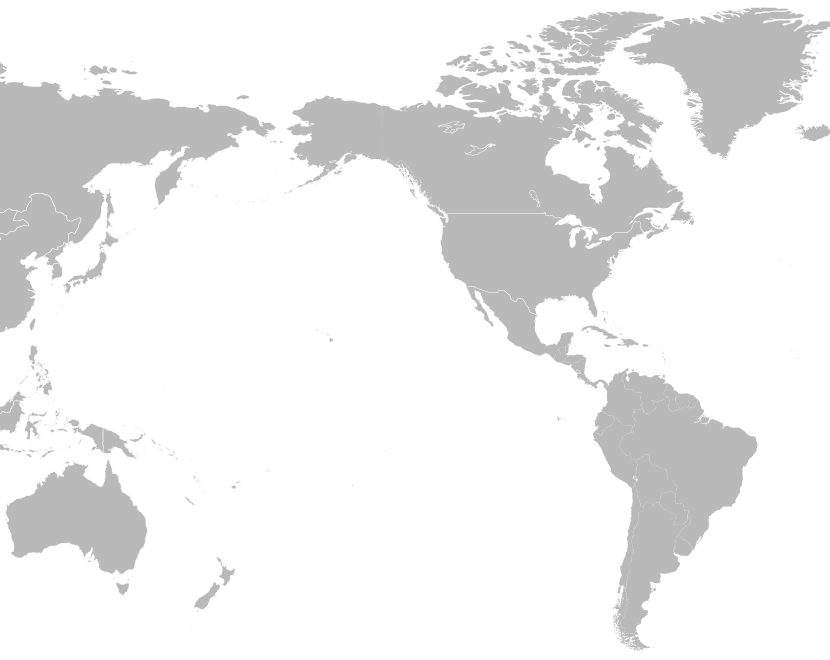

Waves, even those the size of tsunamis, have a tough time making the trip around Cape Horn and into the southern Pacific Ocean. The force of the wave is greatly diminished by the land mass of South America, the islands around Tierra del Fuego, and the narrow channel between those islands and the Antarctic. So by the time the tsunami reaches the South Pacific several days after Greenland dropped an iceberg the size of Rhode Island into the North Atlantic, the wave is no longer the largest ever seen by humans. It is now merely a moderately large tsunami, one capable of doing considerable damage along the coastline but no longer strong enough to reach far inland.

The wave will reach the Gulf of California just before it crashes into Okinawa, on the opposite side of the Pacific. It will swell up between the narrow banks of Baja California and the Sonoran shoreline, destroying several small fishing villages and a few holiday resorts on its way to the mouth of the Colorado River. A few miles up the Colorado, the sleepy burgh of Yuma will be surprised by the sudden rise in river water which will overwhelm Old Town, the Arroyo stadium, and the Colorado River Water bottling company which supports the Arroyo ball team. For Yuma, a desert town completely unprepared for a massive flood, the rising waters will spell death and destruction, essentially wiping the town off the map. Survivors will move elsewhere after the flood, leaving a ghost town with strange water marks high on the walls of the tallest building in town, the new county jail. The Arroyo ball club, ironically named for the many dry river beds scratching the surface of the Sonoran desert surrounding the town, and its management, players and infamous owner Taffy Slummings will take up residence together in a cluster of trailers on a bluff outside town. One of the trailers, it’s rumored, used to be the home of David Goode, the $12 Million Dollar Man—back in the days of PEBA when 12 mil was a HUGE salary. (Whatever happened to David? Well, that’s another story, coming soon to your Kindle.)

Minutes after a tsunami wave reached the Gulf of California and began its march toward the Colorado River and Yuma, Arizona, its twin wave reached Okinawa, on the western side of the Pacific. Residents there have elaborate safety measures in place for tsunami, which are relatively common because of the frequency of earthquakes along the Pacific Rim. So most of the one and a half million residents of the island were able to move up the mountain slopes that form the backbone of the island. From there they had a bird’s eye view of the destruction of their homes and businesses. The eastern facing shore of the island was devastated, while the western facing shore was damaged by heavy flooding but not destroyed by the force of a giant tsunami wave. Still, the island and its accompanying chain of islands that make up the Okinawa Prefecture have been severely damaged and it will be a long time before residents can rebuild homes along the coast. For the time being, they will live in shacks and shanties, tents and cars along the hills beneath the mountain peaks. The Okinawa baseball team, the Shisa, will not be playing in Okinawa for a very long time, obviously.

The wave rushed north of Okinawa into the many bays and harbors along the Japanese coast. And we all know what that means: compromised nuclear reactors. If Fukushima was a Pacific Rim disaster, the release of radiated water from Japan’s several coastal reactors will eventually trigger a world-wide disaster. But for the moment, we can take small solace in the fact that Japan is perhaps the best prepared country for tsunamis in the world. They evacuated all the coast towns and villages well ahead of the wave, except Tokyo, of course, which is just too damn populous to evacuate completely. Those forced to remain moved into the dozens of tsunami-proof buildings Japan has built over the last decades, all on ground higher than sea level, so when the wave did finally reach them, the force was dissipated and the new buildings withstood the rising waters. Tokyo is reporting no loss of life—though that will undoubtedly have to be revised when the waters recede—and damage only to older structures directly adjacent to the coastline. The country and its people have survived, but millions have become homeless and much of the national infrastructure remains underwater. The baseball teams of Neo-Tokyo, Shin Seiki, and Niihama-shi have all been put out of business. Only the Toyama Wind Dancers, located on the west side of the island, will be able to resume playing baseball when the waters reside. The tsunami could not circumvent the island, so only the general rise of water in the Sea of Japan caused damage along the western shoreline of the country.

And in the western half of North America, only the coastal cities of California, Oregon and Washington witnessed the rising waters. As the wave moved north along the American coast, it lost much of its force. San Diego, protected by the Coronado peninsula, suffered flooding but little more. Long Beach was hit hard, especially the Port of Los Angeles area, but the city of LA is far enough inland not to be affected directly. The famous Santa Monica Pier was damaged badly, but the city of Santa Monica, sitting high on the bluffs was untouched. The richest town in America, Malibu, was flooded badly, but most of the rich residents of that town live high above the ocean in the Santa Monica Mountains. Cut off by the floods, they partied their way through the disaster, broadcasting images of their indifference and arrogance and wealth to the millions of displaced persons on the East Coast. Though the tsunami and floods had little effect on the lifestyles of the rich and famous Californians, the anger and resentment spawned in the suffering of most Americans would eventually cost the Malibu who-whos a great deal.

Further up the California coast the force of the tsunami damaged coastal towns but did not move inland to where most Californians lived. San Francisco Bay suffered some flooding, but little more. And cities north of San Fran, like Portland and Seattle, only saw a nominal rise of water.

Meanwhile, the PEBA teams of the Desert Hills—except Yuma, of course—played on, their stadia unaffected by coastal flooding, the games against each other played on schedule. The PEBA Commissioner cancelled the 2039 season for every division except the Desert Hills, which meant no playoffs, no championship, and a very difficult time ahead to restore so many teams in time for the 2040 season. It appeared to be an impossible task.