The Game’s Afoot

by Roberta Umor, Yuma Sun

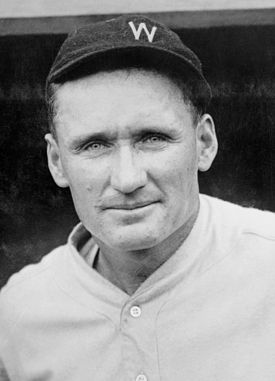

“Christy Mathewson, Rube Marquard, Luke Appling, and … Walter Johnson.”

“Couple points.”

“Three at least.”

“Forget it.”

The younger man looked at the older one, then nodded. “Okay, so Marquard was stretching it a bit, but what’s wrong with Mathewson?”

“Ain’t nothing wrong with Mathewson,” the older one said.

“You gave me Mathewson but not Johnson?”

“Yup.”

“They’re the same thing. Johnson for John, Mathewson for Matthew.”

The old man studied the younger man’s face. He was deciding how much he could get away with. “They called Mathewson Matty, okay, that was his nickname. Matty … Matthew. I give you that one.”

The younger man waited as long as he could. “And Johnson?”

“Ain’t no one never called Walter Johnson just plain John.”

The younger man exploded. “They’re the same kind of word, you idiot! If you take Mathewson, you gotta take Johnson.”

“I swear, sometimes, you think like one of them lib’arians. Everything filed away just so.”

“Listen, you old rum guzzler, this is a name game. You asked for Matthew, Mark, Luke and John, and I gave you Mathewson, Marquard, Appling, and Johnson. I’m scoring that as four points.”

“Four! A moment ago you admitted Marquard was stretching it.”

“I was being conciliatory.”

The older man stood and bellowed, “Don’t you patronize me!” But his aching feet wouldn’t hold him and he started to collapse. He grabbed for the table, a flimsy table covered in cards, and he took it down with him. The cards and the older man littered the floor of the Social Activities Room. The sound brought an orderly running. As the orderly helped the fallen man back to his chair, he noticed the old guy palm one of the cards off the floor as neatly as if he’d been playing 3-Card Monte all his life. The orderly said nothing. The head nurse arrived, a tall thin woman with a frightening abundance of long, kinky red hair which she had no more luck controlling than her patients.

“I’ve told you two before, if you can’t play nice … Now pick this mess up and— “

She stopped to study the cards on the floor. “Those aren’t hospital playing cards. What are they?”

Neither of the men looked at her. Neither spoke. The nurse took one of the cards from the orderly.

The card had a blue and white back with the letters A, P, B, and A printed in white on blue. She turned it over. The name “Ryne Sandberg” appeared at the top with three columns of numbers below. Under the name she recognized the word “Secondbaseman.”

“Baseball cards! You know these are banned. And this is precisely why. Little boys, that’s what you are, playing little boys’ games.”

To the orderly she said, “Confiscate them. All of them. Then search their rooms, they probably have more hidden somewhere. And bring them to me—the cards. I don’t care if I ever see these two again.” Nurse Peters turned and walked away.

“Yes, Nurse Peters,” the orderly said and finished picking the cards from the floor.

“Now look what you’ve done,” the younger patient said to his elder companion.

“Bradley here won’t find any more cards in my room,” the older one said. “Will you, Brad?”

“Don’t drag me into your games,” the orderly said. “I’m in enough trouble as it is with Nurse Ratched there.” He gestured toward Nurse Peters’ retreating back, then stood with a stack of cards in his hands and started to leave. The older man grabbed the sleeve of his white uniform.

“Will you?” he repeated, making it sound more like an order than a question.

Brad shook his head. “I don’t want to have anything more to do with it.”

“So you ain’t got no reason to go looking for more cards, do you?”

“I never find anything anyway,” he said, “you know that.” And with that he carried the cards out of the Social Activities Room.

“See?” the older man said. “He won’t even look.”

“But you just lost us the ’57 Cubbies. My Cubbies.”

“And my Braves. So what? We play some other teams. We was needing a change anyway.”

“A change? In this place? Not as long as Nurse Peters runs the ward. It’s her game and her rules, or there’s no game to play.” The younger man stood with the help of his cane, and though he was the shorter of the two men, he towered over the older one who still sat in his chair, massaging his legs.

“Sit down,” the older man said.

“You’re right about one thing, you old fart. It is time for a change. A BIG change. For starters that means no more of you!” Looking down at the older man, the younger one said, “You lost this one, Bobby Boy. You lost the game, which gives me the series 14 games to 12. And you lost the Name Game. I’m taking all 4 points. Hell, I should get bonus points for Marquard, that was pure genius. And you’re losing me, the only dimwit in this hall of dimwits who will play your games.”

The older man started to say something, but the younger one cut him off. “Who used to play your games. I’m finished.”

He turned and deftly crossed the Social Activities Room without using the cane. The older man waited until the younger one had his hand on the door to the hallway before he yelled after him, “Mark Fidrych was a better pitcher than Rube Marquard!”

The hallway door slammed shut. The old man was alone again. Alone with the pain in his feet. Alone without his baseball cards. Alone with no one to play games with. Alone … with the names of former players spilling out of his memory like so many cards sliding from table to floor.

Mark Fidrych.

Mark McGwire.

Mark Teixeira.

Mark Freeman.

Mark Mauldin.

Lots of easy Marks, he thought. And that’s just first names. How about last names?

Johnny Marcum.

Nick Markakis.

Duke Markell.

Cliff Markle.

Even David Mark Winfield was a better answer than Marquard.

He opened his left hand and looked at the card he’d palmed while he lay sprawled on the floor.

Edwin Lee, Jr., “Eddie”

MATHEWS

Thirdbaseman

He smiled. Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. Not a bad game, after all. He had Matthew, or Mathews—probably some spelling change made at Ellis Island. The immigration officers were always doing stuff like that to “Americanize” the immigrants.

He looked at the card. No one more American than Eddie Mathews. He pocketed the card. He had his Matthew, time to search for the other three. He grimaced as he stood. But as he staggered across the linoleum floor of the Social Activities Room, he forgot the pain in his feet, forgot Nurse Peters and the confiscated cards, forgot even his friend’s angry retreat. All he was thinking about was finding three more cards.

“The game’s afoot,” he said to himself. Then hearing what he’d said, he laughed aloud.

A patient and orderly looked up at him, startled to hear laughter in the Social Activities Room, but he ignored them and banged his way through the doors and out into the hallway like a man with a mission.